2010年6月27日 星期日

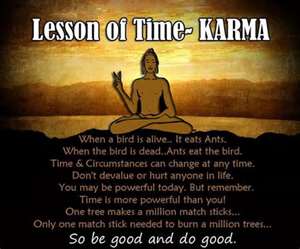

03 Kamma

26 We have seen that beings can be reborn into any of the six realms of existence. But what conditions which of these realms beings will be reborn into?

Before we answer this question, let us see what Buddhism says about why things in general happen the way they do. Theist answer this question by saying that God is the cause of all things, good and bad. But Buddhism denies the existence of a supreme God, so how does it explain the dynamic universe in which we live, a universe full of movements, interactions and events?

Buddhism, like science, teaches natural causation. According to Buddhism, all phenomena operate according to five natural laws (niyama). Physical laws (utu niyama)) govern the physical inorganic order, they determine the temperature at which water will boil, the speed at which light travels, the cycle of the seasons, and so on.

Biological laws (bija niyama) govern growth, reproduction, genetics and so on in living organisms. Psychological laws (cita niyama) govern the functioning of consciousness and phenomena like telepathy, clairvoyance, and others.

Under Universal Laws (dharma niyama) are grouped gravity, the laws of thermodynamics and all the phenomena that are the same throughout the whole universe. But the law that we are most interest in is the Law of Kamma (kamma niyama).

Over the centuries, the Buddhist doctrine of Kamma has been so misunderstood that it has often been represented as a form of determinism. Even today, it is not uncommon to hear people, even Buddist monks who should know better, say that everything that happens to us is due to kamma.

As we will see, this and in fact many popular interpretations of kamma, are quite at odds with what the Buddha taught. What is presented as the doctrine of kamma today is usually not based upon the Buddha's teachings but upon commentorial literature, much of which was written more than a thousand years after the Buddha. We will attempt to explain the doctrine of Kamma as it is described by the Buddha and in the light of modern understanding.

27 The word `kamma‚' means actions, and refers to out intentional (cetama) mental, verbal and bodily behaviour. The Buddha says:

I say that intention is kamma because having first intended, one then acts with body, speech

or mind.

The word `vipaka‚' means result or effect, and refers to the result of our intentional actions. So to give help (kamma) to a stranger might result in making a new and good friend (vipaka). Or again, deliberately telling a lie (kamma) might result in being found out and embarassed or scolded (vipaka). Of course, merely intending to do something is different from actually doing it, although both will have an effect, the first less than the second.

Each time we intentionally think, speak or act, it modifies our consciousness. So what type of person we are now is very much the accumulation of what we have done in the past, and likewise what we do now will go to make up the type of person we will be in the future.

What we are is what we have done.

What we do we will become.

And what type of person we are will greatly influence our relationships with others, our reactions to different situations, and consequently whether or not we are happy. The Buddha puts it this way:

All beings are the owners of their reactions, the heirs of their actions, their actions are the womb from which they spring, with their actions they are bound up, their actions are their refuge. Whatever actions they do, good or bad, they will inherit those actions.

28 At this point it is important to understand the difference between determining factors and conditioning factors. If we say that our past actions determine our present and that our present actions determine our future, this would mean that our whole life was fixed and predestined, and we would not be free to initiate or change anything. Kamma does not determine us.

Our past actions condition our present, which in turn conditions our future, that is to say, our actions have an influence to a greater or lesser degree, and thus there is room to exercise will and initiate change. The Kammic Law therefore is about tendencies rather than inevitable and unchangeable consequences. Thus we can say that Buddhism teaches neither determinism (niyativada) or absolute free-will (attakiriyavada), but rather conditioned will.

The Law of Kamma conditions three things - whether or not we will be reborn, which of the realm of existence we will be reborn into, and what kind of experience we will have. We will examine each of these three things.

29 According to the Buddha, every action that the unenlightened person performs has greed (lobha), hatred (dosa) and delusion (moha), or as the Buddha sometimes calls them ignorance (avijja) and craving (tanha) at its root. Even good actions will have traces of these defilements in them. Greed, hatred and delusion cause us to act, but not all actions will have results in this life; the impetus of those that don't have an effect in this life will impel us into a new body when the old one dies.

To use an analogy from ordinary life, a car moves because of the engine, but if the engine stalls, the residual energy will keep the car moving for a while, until the engine stars again. The Buddha says:

There are three origins of action. What three ? greed, hatred and delusion. An act performed in, born of, originating in, arising from greed, hatred and delusion will have its result wherever one is reborn, wherever the act has its result, there the being will experience the result of it, either in this life, the next life or in future lives.

For as long as we act with greed, hatred and delusion, we create kamma either good or bad, and thus we are reborn. Hence, on attaining Enlightenment, greed, hatred and delusion are finally and completely destroyed, we continue to act but no new kamma is produced, so at death we are no longer re-born.

30 Again, the Buddha says:

There are three origins of action. What three ? Freedom from greed, hatred and delusion. An act performed in, born of, originating in or arising from freedom from greed, hatred and delusion - since greed, hatred and delusion are no more - that act is stopped, cut off at the root, make like a palm-tree stump that can come to no growth in the future.

Kamma causes us to be reborn, and when we are reborn, it is into one or another of the six realms of existence. What type of kamma we have accumulated will condition which of these realms we arise in. All intentional actions have an ethical dimension, and are classified by the Buddha into four different types. He says:

There are four kinds of actions that I have realized by own wisdom and then made known to the world. What four ? They are dark actions having dark effects, bright actions having bright effects, dark and bright actions that have dark and bright effects, and neither dark nor actions that have neither dark nor bright effects.

`Dark actions' refers to behaviour motivated by greed, anger, impatience or other negative mental states and which results in discomfort and unhappiness, or what the Buddha calls `dark results'

`Bright actions' refers to behaviour motivated by positive mental states like kindness, generosity and honesty and which results in ease and happiness, or bright results.

`Dark and bright actions' refers to behaviour which is motivated by a mixture of both positive and negative intentions, and which has a mixture of both positive and negative intentions, and which has a mixed effect.

`Neither dark or bright actions' refers to neutral behaviour which has a correspondingly neutral effect. When certain types of actions are predominant in our behaviour, we are attracted, at death, towards one or another of the six realms of existence. The Buddha says:

And what is the variety of actions ? These are actions having their results in hell, in the animal realm and there are actions having their results in the deva realm.

The cruel, malicious and hate-filled person might be reborn in the hell realm or as a human whose experience is predominantly unpleasant. The person whose main concern in life is eating, sexual satisfaction and coarse enjoyment and who makes no effort to develop intellectually or spiritually might be reborn as an animal or as a human being whose experience is dullness and drudgery.

The fiercely ambitious, constantly dissatisfied person and perhaps those obsessed with or addicted to sex, alcohol or drugs tends to be reborn as a hungry spirit or as a human being tormented by dissatisfaction and discontent. The happy, innocent and loving type tends to be reborn as a deva or as a human being whose experience is mainly joyful and happy.

31 But of course to tell a lie or even to lie a few times does not mean we will be reborn in hell any more than being generous from time to time means we will be reborn in heaven. The Buddha makes it clear that a particular type of behaviour has to be strong, habitual and predominant in the mind, or as he says "committed, carried out and often pursued" before we are likely to be reborn into the very low or very high realms.

Most people, being as they are occasionally very good, occasionally very bad and the rest of the time a little bit of both will probably be reborn as average human beings with average experience. If however, the Dhamma is practised sincerely and properly, the chance of being reborn into a heaven or as a human being in good circumstances is very high.

32 The third thing that the Law of Kamma conditions is the type of experience we will have during our life. People are often heard to say that something which happens to them now is a result of something they did in a pervious life or that something they are doing now will have an effect in the next life. The understanding seems to be that all actions have their effect in any life except the present. This is quite wrong. The Buddha says:

The results of actions are of three types. What three ? Those having an effect in the present life, those having an effect in the next life, and those having an effect in future lives.

In fact, if we observe our experience, we will see the results of much of what we do immediately or soon after - we don't always have to wait until the next life.

Another misunderstanding about kamma is that every act must have its effect, a negative action, for example, must inevitably have a negative effect. Although the Buddha sometimes gives this impression, at other times he makes it clear that the inevitability of effects cannot be so. He says:

If anyone were to say that just a person does a deed, so does he experience it, and if this were true, then living the holy life would not be possible - there would be no opportunity for the overcoming of suffering.

But if anyone were to say that if a person does a deed that is to be experienced, so does he experience it, then living the holy life would be possible - there would be an opportunity for the destruction of suffering. For instance, a small evil deed done by one person may be experienced here in this life or perhaps not at all.

Now, what sort of person commits a small evil that takes him to hell? Take a person who is careless in development of body, speech and mind. He has not developed wisdom, he is insignificant, he has not developed himself, his life is restricted, and he is miserable. Even a small deed may bring such a person to hell.

Now, take the person who is careful in development of body, speech and mind. He has developed wisdom, he is not insignificant, he has developed himself, his life is unrestricted and he is immeasurable. For such a person, a small evil deed may be experienced here or perhaps not at all.

Suppose a man throws a grain of salt into a little cup of water. That water would be

undrinkable. And why? Because the cup of water is small. Now, suppose a man throws a grain of salt into the River Ganges. That water would not be undrinkable. And why ? Because the mass of water is great.

Clearly, if a person's character is predominantly good, a few small bad deeds may have little or no effect, and the same is true of a small good deed done by a person who character is overwhelmingly bad. Again, the effects of some actions will not mature because they may be cancelled out or dissolved by other new actions.

For example, someone might steal something but later come to understand that what he has done is wrong. He might decide to return the stolen article, try to make ammends and resolve to avoid such actions in the future. Under such circumstances, the result of his bad action might be cancelled out by his later good actions. As we said before, the Kammic Law is about tendencies, not inevitable, unchangeable consequences.

33 But perhaps the most common misunderstanding about the Law of Kamma is the belief that every single thing that happens to us tripping over, getting sick, winning the lottery, being good looking, is all the result of past kamma.

The Buddha denies this mistaken belief and for a very good reason. If it was true, it would mean that there would be no point in encouraging people to do good to avoid evil, because their whole life would be predetermined.

The Buddha says:

There are some ascetics and Brahmins who teach and believe that whatever a person experiences, be it pleasant, painful or neutral, all that is caused by past kamma. I went to them and I asked if they did teach such as idea and they said they did and I said:

"If that is so, venerable sirs, then people must commit murder, theft and adultery because of past kamma; they must lie, slander, and use harsh and idle speech because of past kamma. They must be greedy, hating and full of false views because of past kamma."

Those who fall back on past kamma as the decisive factor will lack the desire and effort to do this or not do that.

When we remember that there are five laws governing the universe, it is clear that kamma is only one of several causes of the things that happen to us. Being born beautiful, ugly, well-formed or deformed would probably be due to genetics (biological laws), not to good or bad past actions.

Being intelligent or dull would probably be due to social conditioning and parental influence (physical and psychological laws), not to good or bad past actions. To attribute everything that happens to us to good or bad past actions is, the Buddha says, to ignore causes and effects that our experience tells us are operating. He says:

In this connection, there are some sufferings that arise because of bile, because of phlegm, from wind, because of accidents, because of unforseen circumstances, and also as a result of one's past actions - as you should know from your own experience. And the fact that sufferings arise from these different causes is generally acknowledged by the world to be true.

So those samanas and Brahmins who say: "Whatever pleasure or pain or mental state that a human being experiences, all that is due to one's past actions," they go beyond personal experience and what is generally acknowledge by the world to be true. Therefore, I say that they are wrong.

The Buddha teaches us about the law of kamma so we can understand why we are the way we are, so we can change ourselves, and so we can create the conditions helpful for the attainment of Nirvana.

訂閱:

張貼留言 (Atom)

沒有留言:

張貼留言